Starting a new company rarely goes as planned. The trial and error process of finding anyone who cares about your new product can be embarrassing, lonely, and downright disastrous. My first six months of starting First Research in 1999, which was sold eight years later to publicly traded firm Dun & Bradstreet for $26 million, began just that way….

The brutal honesty of youth

The asphalt radiated a fierce sun as I lugged my electronics back to the car. Sweat pouring, I felt as desperate as Jerry Maguire, Tommy Boy, or Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman. Wearing my best suit and well-prepared to make a presentation, at age 30, I had gotten myself laughed at by high school kids. Something felt as inevitable as death here, but I was confused about where I’d gone wrong.

Six months earlier, though, I felt like I’d invented the light bulb. Dubbed First Research, my fledgling company developed easy-to-comprehend industry reports designed for salespersons to use as background before approaching a client in a particular industry. I was certain this would be the next big thing.

So in 1999, I quit my job selling for a bank and convinced a partner to write these sales-friendly industry reports. Though I was originally confident I would soon be raking in the dough, reality set in, and I saw my plan going nowhere. For more than six months, potential buyers of my industry reports rejected the product: “Our salespeople are experienced and already know about the industries they sell to.”

What? No, they don’t—that’s the problem! I knew I had the solution, but denial and universal rejection were making me frustrated—and then scared.

Yet I pressed on and regrouped, figuring at least I was trying to turn my idea into a real company. If my original plan of selling to salespeople didn’t work, fine; other markets would appreciate my valuable industry reports. Somebody told me that high school business classes might need them. That seemed a reasonable market—our reports were easy-to-read and certainly educational.

Hours spent making phone calls and writing letters led me to the business curriculum director at the Board of Education. His drab office was small and stuffy with paper files stacked on every flat surface, even the windowsills. I explained the relevance of First Research industry reports to his classes’ work.

“Well, you know we have limited budgets just now,” he said. He was telling me this rabbit hole was a dead end, but I had a one-track mind: I would make this work. Through force of will, I convinced him to allow a class of students to pilot First Research.

Hoggard High School, in the relaxed coastal town of Wilmington, North Carolina, is a brick pillbox surrounded by treeless, sandy soil and a trackless parking lot. On this day, the place simmered in an early-autumn sun. Two thousand students were changing classes when I got out of my car. Almost twice their age, I was dressed for success in a dark blue suit, pressed white shirt, and red power tie. I chose a likely teen and asked her the way to the principal’s office.

After signing the visitor log, I found the Intro to Business classroom—a trailer stuck out in the parking lot. Stumbling into these cramped quarters, I introduced myself to the teacher, Mrs. McAllen, a heavy-set woman in her mid-40s. “So you’re the salesman I’ve heard about,” she said with a wry grin. “Okay, come on in—you’ll get your chance in a couple of minutes.”

I took a seat in the back. For 10 minutes, she talked about assignments. Every so often, a student’s eye grazed my way, then moved off. Finally, Mrs. McAllen introduced me.

“Attention, class. CLASS! Listen up! We have a guest speaker today. . . . What was your name again?”

“I’m Bobby Martin from First Research.”

“Class, Mr. Martin is going to tell us about his software.”

Software? Oh boy; this may be a tougher sell than I anticipated.

I fumbled around connecting cords from my laptop to my portable projector. Mousing and snickering, the students didn’t sound at all ready to listen up. I looked out at the group, but no Mrs. McAllen—she was long-gone, probably to the teachers’ break room.

“Hi, everybody. As your teacher said, I’m Bobby Martin from a new company, First Research, and I’m here to show you something exciting.”

I broke into a 15-page PowerPoint deck with slides more suited to a trade event, even though I’d titled one of my slides, “Benefits for Students.” Apathetic to these benefits, the students talked throughout my presentation. Periodically, one or two looked up, confused– “Why are we doing this?” on their faces. Perhaps worse, a couple of them appeared to feel sorry for me.

The trailer was hot and airless. My mouth was dry. In the back, an all-American in a polo shirt and khakis asked, “Excuse me, sir. What are you talking about?” Laughing and slouching in a chair, his buddy jabbed him on the arm.

I chuckled and shook my head. Sweat had officially saturated my shirt.

“Hey, everybody! I’m telling you, YOU NEED THESE REPORTS…AND THEY DON’T EXIST ANYWHERE ELSE!”

After 15 minutes of awkward, borderline abusive, interaction with the students, game over. They didn’t want my industry reports and wouldn’t use them to learn about the various industries in our economy. I disconnected my cords, packed up, and slunk out, my pride bruised and my enthusiasm squelched. No one seemed to notice.

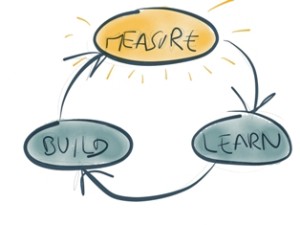

After several months of experimenting with product and selling choices, some good ones and some bad ones (like attempting to sell First Research to high school students as a cooler kind of textbook), a few early adopters purchased my industry reports. As I originally had suspected, my product WAS a viable idea!

Surviving a maelstrom of criticism & self-doubt

From speaking with dozens of other successful founders, this type of story is all par for the course. You may have your own similar stories. Here is some fitting advice for surviving–mentally, physically, and financially– while you experiment.

- From Madonna: “I laugh at myself. I don’t take myself completely seriously. I think that’s another quality that people have to hold on to … you have to laugh, especially at yourself.” A study in the journal Emotion says that people who are able to laugh at themselves are more cheerful and healthier. These early start-up disasters are badges of honor and make for great stories (and blog posts) down the road. I love this story from Hoggard High School because today, with the benefit of hindsight, it was a valuable lesson learned, and it’s pretty damn funny to picture a sweat-soaked 30 year-old man in a suit getting laughed off the stage by a bunch of teenagers.

- From Teddy Roosevelt: “It’s not the critic that counts… The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood.” So know this is what it takes –learn to mop your sweaty brow and brush off that dust.

- From Kenny Rogers: “You’ve got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, know when to walk away, know when to run…” Trial and error is part of the game, but so is knowing when to stick it out and try harder on your current path versus quitting and trying something else. I gave up on selling to high schools right then and there. Trust your gut instinct.

When First Research was initially formed in 1999, I was a burned-out 29-year old banker with little business experience. What I did have was a novel idea for an online product that would help salespeople quickly prepare for calls by researching their prospect’s industry, and on April 15, 1999, after quitting my day job, First Research opened for business. Eight months later, our progress was as follows:

When First Research was initially formed in 1999, I was a burned-out 29-year old banker with little business experience. What I did have was a novel idea for an online product that would help salespeople quickly prepare for calls by researching their prospect’s industry, and on April 15, 1999, after quitting my day job, First Research opened for business. Eight months later, our progress was as follows:

I was struck by James Surowiecki’s mention in a recent New Yorker piece, “

I was struck by James Surowiecki’s mention in a recent New Yorker piece, “