Seeing Alanis Morissette’s recent duet with James Corden of her 1995 song “Ironic” on The Late Show reminded me of a hilarious video parody of the same song. In 2013, after 17 years of being nettled by Morissette’s casual use of the word “irony,” sisters Eliza and Rachael Hurwitz, both 24 at the time, fixed the song’s snafus by producing and distributing “It’s Finally Ironic,” a video mimicking the original. In the new video, these young satirists kept the song’s melody, but changed its lyrics to relay truly ironic anecdotes, such as: “He won the lottery, and died the next day, from a severe paper cut from his lottery ticket.”

Rachael and Eliza wrote the video in order to set the record straight on the meaning of “irony” and to gain exposure for their entertainment careers. They invested about two weeks in writing, shooting, editing, and producing the video, saving money by borrowing video equipment and a car from their father to use as the setting for their parody. Their parents and another sister helped them film. “The editing process took us about a week, and we just used iMovie,” Rachael says. “Overall, we really did not have money to spend on creating the music video, so it was a very low-budget endeavor.”

Their spoof has had nearly a million YouTube views and still counting, and it’s been featured on a number of national media outlets such as The Wall Street Journal, ABCNews.com, McLean’s website, MSN, and The Huffington Post.

Shortly after watching the Hurwitz parody, I was surfing the web and landed on publicly traded payroll processing firm Automatic Data Processing’s (ADP’s) website and saw it had 630,000 customers and nearly $11 billion in revenue. This is serious business! Kudos to ADP; they’ve done a good job of managing their company in that its stock has returned 4,667 percent since 1983, versus a 1,174 percent return in that period for the S&P 500.

Entrepreneurship is a process that goes on every day somewhere in between the creating/producing of “It’s Finally Ironic” and ADP’s large, complex, tightly-managed organization. Many startups begin as spur-of-the-moment ideas, like this video spoof, but grow to be as complex as ADP. In fact, ADP was started in 1949 by 21-year-old Henry Taub on a low budget to solve an “of-the-moment” problem that he had identified–an issue that he found interesting. Henry’s idea to process payroll for companies came to him when he was visiting a nearby company and learned that its payroll manager had fallen ill, so payroll wasn’t produced on time, resulting in service disruption.

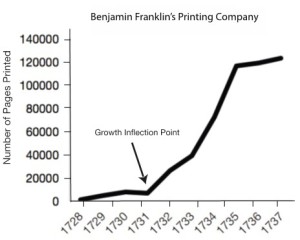

He may have thought, “Ah-ha! I can fix that.” Henry’s first client, New Era Dye and Finishing, was across town, but he didn’t have a car, so like the Hurwitz sisters, he improvised, taking the city bus to pick up their paperwork and deliver their payroll until he reached hockey stick revenue growth.

Entrepreneurship needs a mixture of artful creativity, like the Hurwitz sisters’ investment in their video, and also the direct business-mindedness of ADP. What’s important in the case of each startup is finding the right balance to meet the requirements of the founder’s personality and life goals. Balance? Unless you are a Wallenda, that’s easier said than done.